Study suggests that 7% of global GDP will disappear by 2100 as a result of business-as-usual carbon emissions – including over 10% of incomes in both Canada and the United States.

If advanced nations want to avoid major economic damage in the coming decades, the Paris Agreement is a good start

Kamiar Mohaddes

Prevailing economic research anticipates the burden of climate change falling on hot or poor nations. Some predict that cooler or wealthier economies will be unaffected or even see benefits from higher temperatures.

However, a new study co-authored by researchers from the University of Cambridge suggests that virtually all countries – whether rich or poor, hot or cold – will suffer economically by 2100 if the current trajectory of carbon emissions is maintained.

In fact, the research published on Monday by the National Bureau of Economic Research suggests that – on average – richer, colder countries would lose as much income to climate change as poorer, hotter nations.

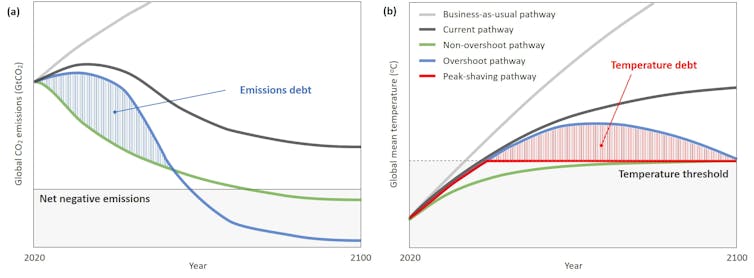

Under a “business as usual” emissions scenario, average global temperatures are projected to rise over four degrees Celsius by the end of the century. This would cause the United States to lose 10.5% of its GDP by 2100 – a substantial economic hit, say researchers.

Canada, which some claim will benefit economically from temperature increase, would lose over 13% of its income by 2100. The research shows that keeping to the Paris Agreement limits the losses of both North American nations to under 2% of GDP.

Researchers say that 7% of global GDP is likely to vanish by the end of the century unless “action is taken”. Japan, India and New Zealand lose 10% of their income. Switzerland is likely to have an economy that is 12% smaller by 2100. Russia would be shorn of 9% of its GDP, with the UK down by 4%.

The team behind the study argue that it isn’t just about the number on the thermometer, but the deviation of temperature from its “historical norm” – the climate conditions to which countries are accustomed – that determines the size of income loss.

“Whether cold snaps or heat waves, droughts, floods or natural disasters, all deviations of climate conditions from their historical norms have adverse economic effects,” said Dr Kamiar Mohaddes, a co-author of the study from Cambridge’s Faculty of Economics.

“Without mitigation and adaptation policies, many countries are likely to experience sustained temperature increases relative to historical norms and suffer major income losses as a result. This holds for both rich and poor countries as well as hot and cold regions.”

“Canada is warming up twice as fast as rest of the world. There are risks to its physical infrastructure, coastal and northern communities, human health and wellness, ecosystems and fisheries – all of which has a cost,” he said.

“The UK recently had its hottest day on record. Train tracks buckled, roads melted, and thousands were stranded because it was out of the norm. Such events take an economic toll, and will only become more frequent and severe without policies to address the threats of climate change.”

Mohaddes worked on the study with Cambridge PhD candidate Ryan Ng, as well as colleagues from the University of Southern California, USA, Johns Hopkins University, USA, National Tsing Hua University, Taiwan, and the International Monetary Fund.

Using data from 174 countries dating back to 1960, the research team estimated the link between above-the-norm temperatures and income levels. They then modelled the income effects under a continuation of business-as-usual emissions as well as a scenario in which the world “gets its act together” and holds to the Paris Agreement.

Researchers acknowledge that economies will adapt to changing climates, but argue that their modelling work shows adaptation alone will not be enough.

The scientific consensus suggests that adapting to climate change takes an average of 30 years, as everything from infrastructure to cultural practice slowly adjusts. But even if this adjustment speeds up to just 20 years, the United States still loses almost 7% of its economy, with over 4% of global GDP gone by the century’s end.

The team also undertook a more focused approach to the U.S. to gauge the strength of their results. “Cross-country studies are important for the big picture, but averaging data at national levels leads to loss of information in geographically-diverse nations, such as Brazil, China or the United States,” said Mohaddes.

“By concentrating on the U.S., we were able to compare whether economic activity in hot or wet areas responds to temperature fluctuations around historical norms in the same way as that in cold or dry areas within a single large nation.”

They looked at ten sectors ranging from manufacturing and services to retail and wholesale trade across 48 U.S. states, and found each sector in every state suffered economically from at least one aspect of climate change – whether heat, flood, drought or freeze.

When scaled up, these are the effects that will create economic losses at the national and global levels, even in advanced and allegedly resilient economies, say the researchers.

“The economics of climate change stretch far beyond the impact on growing crops,” said Mohaddes. “Heavy rainfall prevents mountain access for mining and affects commodity prices. Cold snaps raise heating bills and high street spending drops. Heatwaves cause transport networks to shut down. All these things add up.”

“The idea that rich, temperate nations are economically immune to climate change, or could even double and triple their wealth as a result, just seems implausible.”

Mohaddes is from Sweden, which some predict will benefit from higher temperatures. “But what about the winter sports depended upon by the Swedish tourism industry?”

“If advanced nations want to avoid major economic damage in the coming decades, the Paris Agreement is a good start.”

The text in this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Images, including our videos, are Copyright ©University of Cambridge and licensors/contributors as identified. All rights reserved. We make our image and video content available in a number of ways – as here, on our main website under its Terms and conditions, and on a range of channels including social media that permit your use and sharing of our content under their respective Terms.