source: www.cam.ac.uk

Offspring whose mothers had a complicated pregnancy may be at greater risk of heart disease in later life, according to a new study in sheep. The research, led by a team at the University of Cambridge, suggests that our cards may be marked even before we are born.

Our discoveries emphasise that when considering strategies to reduce the overall burden of heart disease, much greater attention to prevention rather than treatment is required

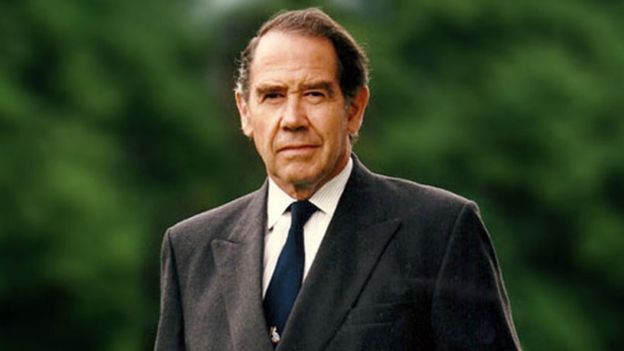

Dino Giussani

Heart disease is the greatest killer in the world today, and it is widely accepted that our genes interact with traditional lifestyle risk factors, such as smoking, obesity and/or a sedentary life to promote an increased risk of cardiovascular disease.

In addition to the effects of adult lifestyle, there is already evidence that the gene-environment interaction before birth may be just as, if not more, important in ‘programming’ future heart health and heart disease. For example, human studies in siblings show that children born to a mother who was obese during pregnancy are at greater risk of heart disease than siblings born to the same mother after bariatric surgery to reduce maternal obesity. Such studies have provided strong evidence in humans that the environment experienced during critical periods of development can directly influence long-term cardiovascular health and heart disease risk.

The new research, funded by the British Heart Foundation and the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, shows that adult offspring from pregnancies complicated by chronic hypoxia – lower-than-normal oxygen levels – have increased indicators of cardiovascular disease such as high blood pressure and stiffer blood vessels. Chronic hypoxia in the developing baby within the womb is one of the most common outcomes of complicated pregnancy in humans. It occurs as a result of problems within the placenta, as can occur in preeclampsia, gestational diabetes or maternal smoking.

The study, led by Professor Dino Giussani from the Department of Physiology, Development and Neuroscience and published today in the journal PLOS Biology, used pregnant sheep to show that maternal treatment with the antioxidant vitamin C during a complicated pregnancy could protect the adult offspring from developing hypertension and heart disease. The work therefore not only provides evidence that a prenatal influence on later heart disease in the offspring is indeed possible but also shows the potential to protect against it by “bringing preventative medicine back into the womb,” as Dr Kirsty Brain, first author of the study, puts it.

It turns out that vitamin C is a comparatively weak antioxidant, and while the Cambridge study provides a proof-of-principle, future work will focus on identifying alternative antioxidant therapies that could prove more effective in human clinical practice.

“Our discoveries emphasise that when considering strategies to reduce the overall burden of heart disease, much greater attention to prevention rather than treatment is required,” adds Professor Giussani. “Treatment should start as early as possible during development, rather than waiting until adulthood when the disease process has become irreversible.”

Professor Giussani stresses that it is too soon to consider vitamin C as a potential supplement for mothers. Any mothers concerned about their baby’s development in the womb should speak to their doctor before changing their diet or using supplements.

The work draws attention to a new way of thinking about heart disease with a much longer-term perspective, focusing on prevention rather than treatment.

Reference

Brain KL, Allison BJ, Niu Y, Cross CM, Itani N, Kane AD, et al. Intervention against hypertension in the next generation programmed by developmental hypoxia. PLoS Biol 17(1): e2006552. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.2006552

The text in this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Images, including our videos, are Copyright ©University of Cambridge and licensors/contributors as identified. All rights reserved. We make our image and video content available in a number of ways – as here, on our main website under its Terms and conditions, and on a range of channels including social media that permit your use and sharing of our content under their respective Terms.

Dr Katerina Kassavou began her career studying psychology at the University of Crete before moving to Cambridge in 2014. She is now part of the Behavioural Science Group at Cambridge, looking at how we can change people’s behaviours to improve their health.

Dr Katerina Kassavou began her career studying psychology at the University of Crete before moving to Cambridge in 2014. She is now part of the Behavioural Science Group at Cambridge, looking at how we can change people’s behaviours to improve their health.